Credit: Louis Freedberg / EdSource

While most attention in the United States is focused on the presidential elections today, I’ll be watching two local school board races that will be historic for a completely different reason.

For the first time, young people aged 16 and 17 in Oakland and nearby Berkeley will be voting in school board elections.

Although some smaller communities in Maryland have extended a limited vote to a similar age group, Oakland with a population of over 400,000, is the largest community in the nation to do so by far.

The initiative came about as a result of youth organizing that put pressure on their city councils to place measures on the ballot allowing young people aged 16 and over to vote in their local school board elections. Berkeley voters passed a law approving the change in 2017 and Oakland voters in 2020. It has taken years to get the idea to fruition.

When I heard about this effort, I was deeply skeptical.

After all, school board meetings are, for the most part, sleepy affairs — unless there is a controversy that rouses parents and students, like school closures or political battles over curricula, book bans and other hot-button issues.

It is hard enough to get parents interested in school board politics. It seemed to me even less likely that teenagers would embrace doing so with gusto to justify the effort and expense of giving them the vote.

But after attending a school board candidates’ forum organized by students in Oakland last week — and speaking to the candidates vying for their votes, I now have a different view.

I’m convinced that having young people involved in school board politics and decision-making is more than just a nice idea.

For one thing, we know that the earlier young people participate in the democratic process, the more likely they are to do so as adults. It is also a powerful way to get young people involved in shaping institutions that affect them profoundly, and which they have intimate knowledge of: the schools where they spend much of their time during their adolescence.

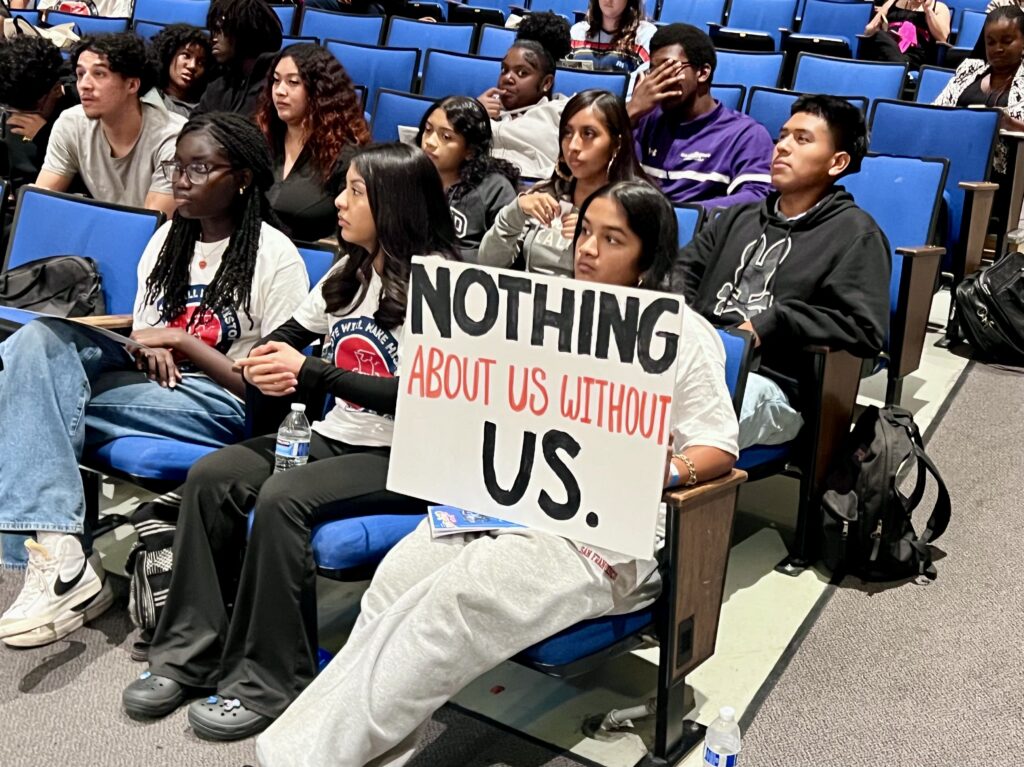

The forum itself was a rousing affair, and ran from 5 to 8 p.m. Six of the seven candidates running for the board showed up for the event. (The seventh was out of the country and sent a representative.) There were 200 hundred students, most of whom stayed until the end of the marathon interrogation. Many wore T-shirts with the slogan, “My Vote Will Make History” on the front and, on the back, “No decisions about us without us.”

Each candidate had one minute to respond to a set of questions students projected on a screen. If candidates went over the time limit, their microphones were shut off, so the candidates mostly obeyed the rules. And they answered the questions seriously without being patronizing.

These students’ votes are arguably going to be a lot more informed than those of most older voters who may not have stepped into a school in years. Most adult voters will have only the barest idea about current school concerns or what goes on inside their walls.

Let’s be honest: with rare exceptions, votes for school boards are typically the last thing many, if not most, voters pay attention to.

“A lot of adults are making decisions about our schools when they’re not even the ones in the school,” Edamevoh Ajayi, a senior at Oakland Technical High School who has been a leader in the Oakland youth vote project, told me. “So they wouldn’t even know what to change.”

“At least for students, we haven’t really been welcomed,” she said, referring to district governance in general. “It’s kind of been an adult-led space.”

It would be one thing if things were going well in their district, and adult leaders had proven themselves. But once again, the district is in crisis, as it copes with declining enrollment, poor attendance, a massive budget deficit, and the prospect of having to close or merge schools next year. There is a real chance of a state takeover — a repeat of what happened 20 years ago when the district had to get a $100 million loan from the state to bail it out. Getting students’ voices into the mix certainly couldn’t hurt, and is more likely to help. That’s in addition to the long-term benefits of getting young people involved in our democracy at an earlier age.

As Patrice Berry, a former teacher running for the Oakland school board for the first time, told me, “They’re going to make us better overall.”

•••

Louis Freedberg is EdSource’s interim executive director.

The opinions expressed in this commentary represent those of the author. EdSource welcomes commentaries representing diverse points of view. If you would like to submit a commentary, please review our guidelines and contact us.