In the 1860s, Charles Baudelaire bemoaned what we might now call doomscrolling:

Every newspaper, from the first line to the last, is nothing but a tissue of horrors. Wars, crimes, thefts, licentiousness, torture, crimes of princes, crimes of nations, individual crimes, an intoxicating spree of universal atrocity.

And it’s this disgusting aperitif that the civilised man consumes at breakfast each morning … I do not understand how a pure hand can touch a newspaper without a convulsion of disgust.

The poet’s revulsion was widely shared in 19th-century France. Amid rapid increases in circulation, newspapers were depicted as a virus or narcotic responsible for collective neurosis, overexcitement and lowered productivity. Criminality was blamed on the suggestive effects of lurid crime reports. And many writers concluded that the newspaper would soon kill off the book and imaginative literature altogether.

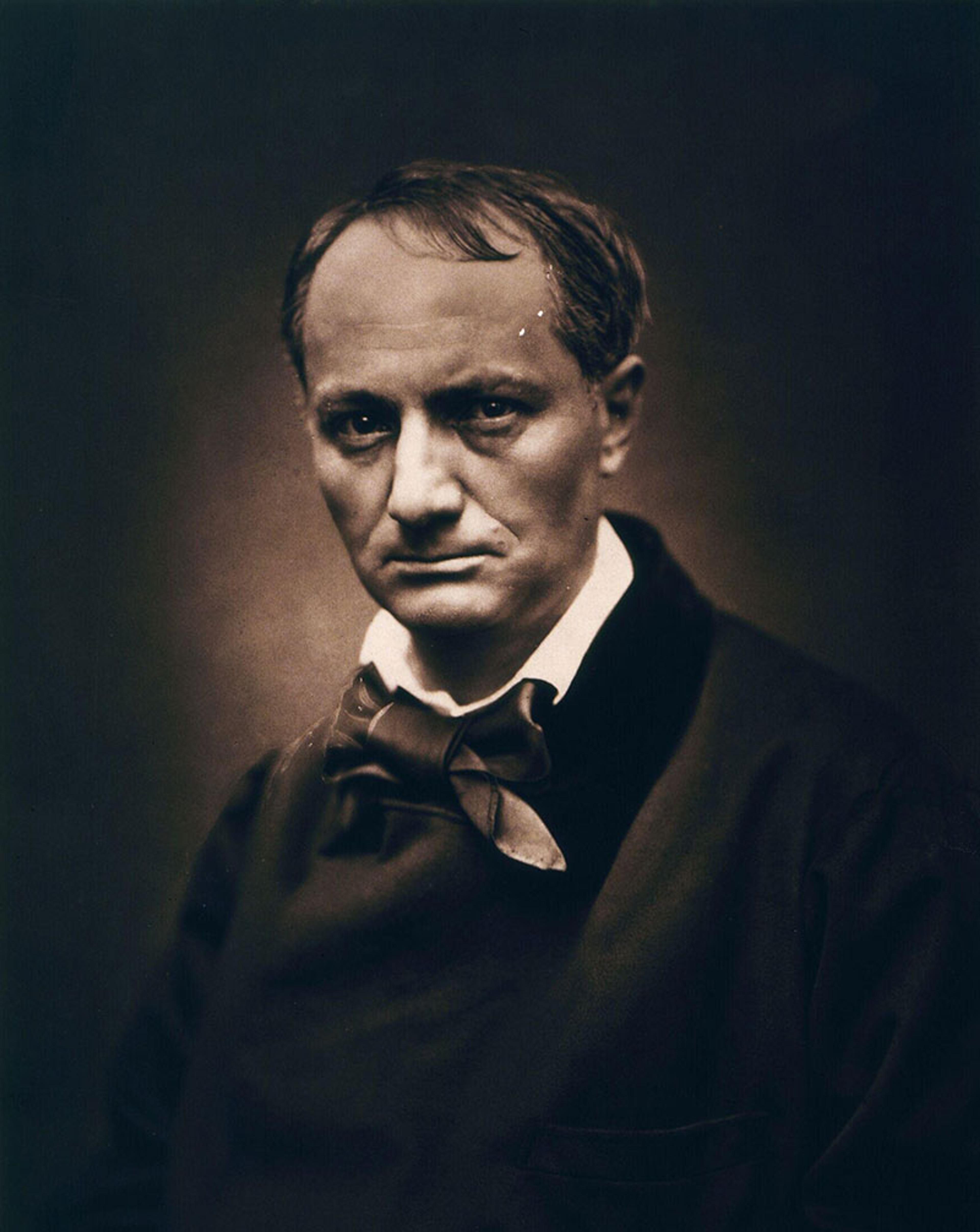

Portrait of Charles Baudelaire (1862) by Étienne Carjat. Courtesy the V & A Museum, London

These dismal appraisals yielded a series of fiercely pessimistic novels of journalism by authors such as Honoré de Balzac, the Goncourt brothers and Guy de Maupassant. Each portrayed the press as a corrupt and corrupting behemoth that was devouring art and culture within its predatory maw. ‘Newspapers are an evil,’ as one world-weary author remarks in Balzac’s Lost Illusions (1837-43). Another describes newspaper offices as ‘whorehouses of thought’, anticipating the degradation of the hero, Lucien de Rubempré, from idealistic young poet to unscrupulous hack as he falls for a glamorous courtesan.

But French writers’ loathing of journalism was underlain by a fundamental tension: those who criticised the press most vehemently were themselves journalists, and their novels of journalism were typically published in the same newspapers they excoriated. Journalism and literature were so deeply entwined that newspapers became ‘the laboratory of literature’ throughout the long 19th century, generating new literary forms, such as prose poetry and the serial novel.

Novels, short stories, poetry and criticism, along with much whimsical blather, filled up pages largely devoid of hard political news (due to extensive censorship) and proved an ideal means of attracting readers. Since books and theatre seldom earned a decent income, most writers reluctantly turned to the burgeoning marketplace of newspapers and magazines. That fraught relationship is summed up in a quip from Gustave Flaubert’s posthumously published compendium of contemporary fatuity, the Dictionary of Received Ideas (1910): ‘Newspapers – Can’t live without them, but thunder against.’ Writer-journalists such as Balzac and Maupassant railed against the world from whence they came.

Their fictional denunciations of journalistic skullduggery and philistinism were hardly without basis. For the French press was sustained by wholesale bribery. One leading editor even declared that he was not happy unless every line of his newspaper had been bought and paid for. Novels of journalism shed murky light on that otherwise hidden world of venality (which reporters and editorialists were naturally loath to confront).

But the repetitive, self-pitying trope, inaugurated by Balzac, equating journalism with prostitution itself obscured the complexities of literary-journalistic exchange. Newspapers were at once a meretricious medium and a forum for creative innovation. During the second half of the 19th century, some modernist writers began to reckon with that duality, toning down the anti-journalistic thunder and taking a more nuanced and self-conscious approach to the rise of mass press. As we, in turn, struggle to come to terms with the tumultuous proliferation of new media, that spirit of ambivalent openness offers timely lessons. The French modernists show us how to carve out space for artistic expression within dominant media without being dominated by them.

Despite fulminating against the sadistic intoxication dispensed by newspapers, Baudelaire was among the first to celebrate journalism’s artistic capacities. In an 1863 essay for Le Figaro, then a biweekly literary newspaper and the ancestor of today’s conservative broadsheet, he delivered a rapturous ode to the newspaper sketch artist Constantin Guys, dubbing him ‘the painter of modern life’. For Baudelaire, Guys embodied a perpetually elusive, volatile feature of existence that the poet – reaching for a then-novel, usually pejorative term circulating in the press – called ‘modernity’.

Alternately described as ‘the eternal within the transitory’ and as ‘the transitory’ itself, modernity never acquires a consistent definition in Baudelaire’s essay. But amid that conceptual uncertainty, his enthusiasm for Guys’s endeavours stands out with resounding clarity. What inspired Baudelaire was not so much the formal qualities of Guys’s now largely forgotten illustrations of Parisian streetlife, fashionable clothing and the Crimean War as the intrepid hustle underlying them. Complementing his quasi-heretical salute to modernity, Baudelaire elevated the newspaperman above traditional studio artists, whom he dismissed as ‘hamlet brains’ chained to their palettes.

The newspaper is not just the conceptual crucible of modernity but also its most palpable metonym

His valorisation of journalism parallels his vacillations about modernity. For the medium of the newspaper is eternally caught up in a quest for an uncertain, ever-changing commodity – the news – that loses its novelty and value almost as soon as it is apprehended, whereupon the whole cycle begins again. Like Baudelaire’s painter of modern life, the whole journalistic enterprise is animated less by the goal of creating an enduring body of work than by the relentless dynamism of the process itself. And yet the newspaper also represents a locus of stability and collective identity that condenses the life of the city, the nation and the world into a few unbound pages. At once ephemeral and eternal, the newspaper is not just the conceptual crucible of modernity but also its most palpable metonym.

As Baudelaire’s modernist successors – who included Stéphane Mallarmé, Guillaume Apollinaire and Marcel Proust – found themselves caught up in the modern condition of constant impermanence, they, too, recognised that the press had become an inescapable feature of their world. Rather than seek an unobtainable refuge, these ‘hustlers in the ivory tower’ (as I have called them in a recent book) duly struggled to harness that medium to their own creative and commercial ends.

Underlying that shift towards a more flexible aesthetic outlook was the continuing expansion of ‘newspaper civilisation’, which reached its apogee under the Third Republic that was founded in 1870 amid humiliating defeat in the Franco-Prussian War. The abolition of most forms of censorship, declining paper costs, railway expansion and universal primary education triggered a newspaper boom that saw total daily circulation rise from around 1.5 million in 1870 to nearly 10 million by 1914. What had been a relatively expensive item, mostly consumed by a metropolitan elite, became a massified industrial product, as cheap and ubiquitous as bread and wine, that penetrated every aspect of political and cultural life.

With the elimination of restrictions on news reporting, many writers now became alarmed that a new, Americanised, information-driven journalistic culture was driving them out of the press. In 1886, Mallarmé lamented that writing was being swallowed up by the crude, utilitarian rhythms of ‘universal reportage’, which he portrayed as the antithesis of literature. Mallarmé was, in turn, frequently ridiculed in the press for the obscurity of his work, which departs from semantic and syntactical convention to create dream-like musical and painterly effects. For the poet’s young acolytes – loosely known as Symbolists – that opposition became an article of faith. Following Mallarmé’s death in 1898, one of them, Charles Morice, commemorated his mentor as a paragon of artistic purity who had ‘always refused to participate in that cold, hard lie, the so-called literary newspaper’.

That image of austere detachment from literary-journalistic commerce is belied by Mallarmé’s extensive involvement with the press. In 1874, he founded and edited a short-lived fashion magazine, writing all the articles himself under a variety of pseudonyms. And despite his later broadside against ‘universal reportage’, the poet went on to publish work in daily newspapers. He also portrayed the newspaper as the site of a nascent poetic revolution – the ‘modern popular Poem’ – that would be embraced by a vastly expanded reading public in an atmosphere of festive, democratic celebration.

The scattered layout also points to Mallarmé’s fascination with newspaper typography

The ‘modern popular Poem’ formed part of a broader vision of literary-journalistic hybridity that would bring together newspaper and book, combining the most dynamic properties of both media within a new form. Mallarmé projected that this mysterious ‘Book’ or ‘Great Work’ would form the basis for a new civic religion grounded in poetry that would fill the spiritual vacuum he perceived at the heart of the Third Republic. Though he never brought that utopian and doubtless unrealisable endeavour to completion, Mallarmé’s final masterpiece, A Throw of the Dice Never Will Abolish Chance (1897), offers a glimpse of his transcendent ambitions.

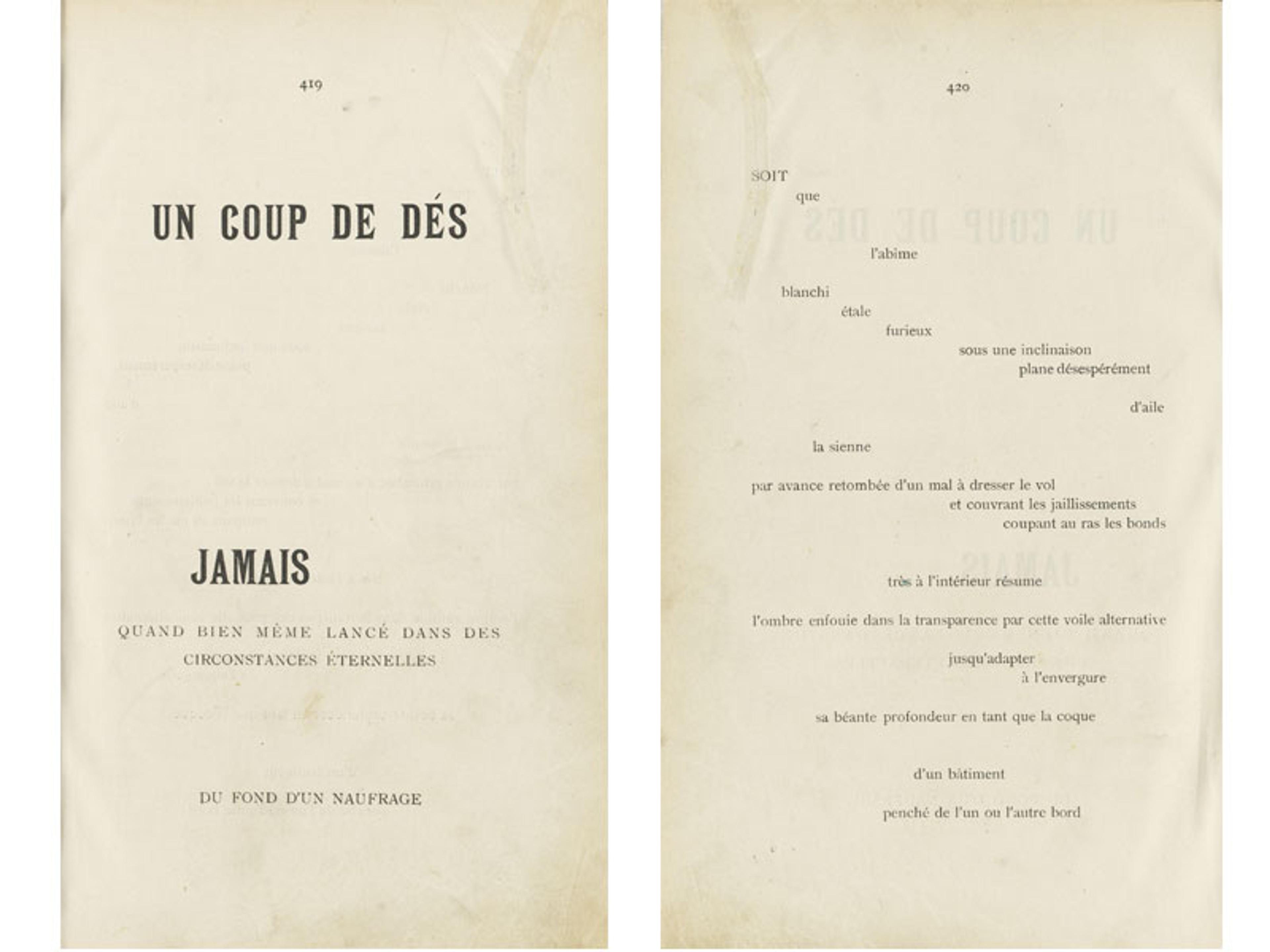

Pages from Un coup de dés jamais n’abolira le hasard (A Throw of the Dice Never Will Abolish Chance), by Stéphane Mallarmé, in the May 1897 issue of the magazine Cosmopolis. Courtesy the BnF, Paris

With its elegant textual gradations sweeping across the pages, the poem has the feel of an abstract painting or a musical score. The scattered layout, in which some words are printed in large, bold type, also points to Mallarmé’s fascination with newspaper typography. Like the front page of a newspaper that compels us to pay attention to crises and disasters, A Throw of the Dice is haunted by a sense of swirling upheaval. And its central motif – a shipwreck (‘naufrage’) – could be a piece of news-in-brief, an otherwise minor slice of ‘universal reportage’ that acquires richly enigmatic metaphorical significance when embedded within the cosmic drama of the poem. What had been wrecked was the cohesion of literary culture in the face of newspaper civilisation. Mallarmé’s response was to unite high art with a devalued product of mass culture, thereby making a seminal contribution to what was later dubbed ‘intermediality’.

The poem’s genesis exemplified that aesthetic outlook. A Throw of the Dice was published – for the first and only time during the author’s lifetime – in the May 1897 edition of Cosmopolis, a large-circulation, commercially oriented magazine that had solicited his contribution, offering the tidy sum of 40 francs per page of verse (around $200 in today’s money). It seems probable that the poem had not been written (or at the very least completed) prior to Mallarmé receiving the magazine’s proposal. His single most esoteric and revolutionary work was forged through a lucrative transaction with the mass press.

Mallarmé was also a nimble self-publicist, always ready with a lapidary phrase for interviewers while maintaining a Delphic aura. Asked for his reaction to a bomb attack on the Chamber of Deputies, he offered a single line: ‘I know of no other bomb, than a book.’ In 1894, after publishing a front-page article in Le Figaro advocating public subsidy for writers, Mallarmé encouraged his acolyte Morice to undertake a survey of other authors on the subject for the same newspaper, further boosting his profile. That discreetly cultivated fame was confirmed two years later when Le Figaro, by then a leading political and cultural daily, celebrated his election as ‘prince of poets’ (following a survey of his peers conducted by the literary magazine La Plume).

While Mallarmé’s vision of literary-journalistic hybridity found few echoes in the work of his Symbolist followers, the later poets clustered around Apollinaire embraced an aesthetic of playful intermediality that owed much to the precedent of A Throw of the Dice. Apollinaire set the tone in the provocative, kaleidoscopic overture of his poem ‘Zone’ (1912):

Tu lis les prospectus les catalogues les affiches qui chantent tout haut

Voilà la poésie ce matin et pour la prose il y a les journaux

Il y a les livraisons à 25 centimes pleines d’aventures policières

Portraits des grands hommes et mille titres divers

[You read the handbills catalogues posters that sing out loud

That’s poetry this morning and for prose there’s the newspapers

There are five-penny serials full of crime and adventure

Pictures of great men and a thousand sundry headlines]

Even if poetry is identified here with advertising rather than newspapers, the image of a Parisian newspaper kiosk with its riot of competing headlines and illustrations adds a splash of journalistic colour to the poem itself. Like newspaper headlines, ‘Zone’ is devoid of punctuation. Apollinaire’s free verse thereby assimilates the visual immediacy of newspaper typography. Yet that burst of innovation is balanced by frequent use of the ‘noble’ classical metre of the 12-syllable alexandrine. Mallarmé similarly abandoned conventional versification in A Throw of the Dice while discreetly structuring his poem around the denominator 12. As Jean-Paul Sartre once quipped of Baudelaire, both Mallarmé and Apollinaire were moving forward while looking in the rear-view mirror.

Apollinaire continually found inspiration in the rough-and-tumble of newspaper civilisation

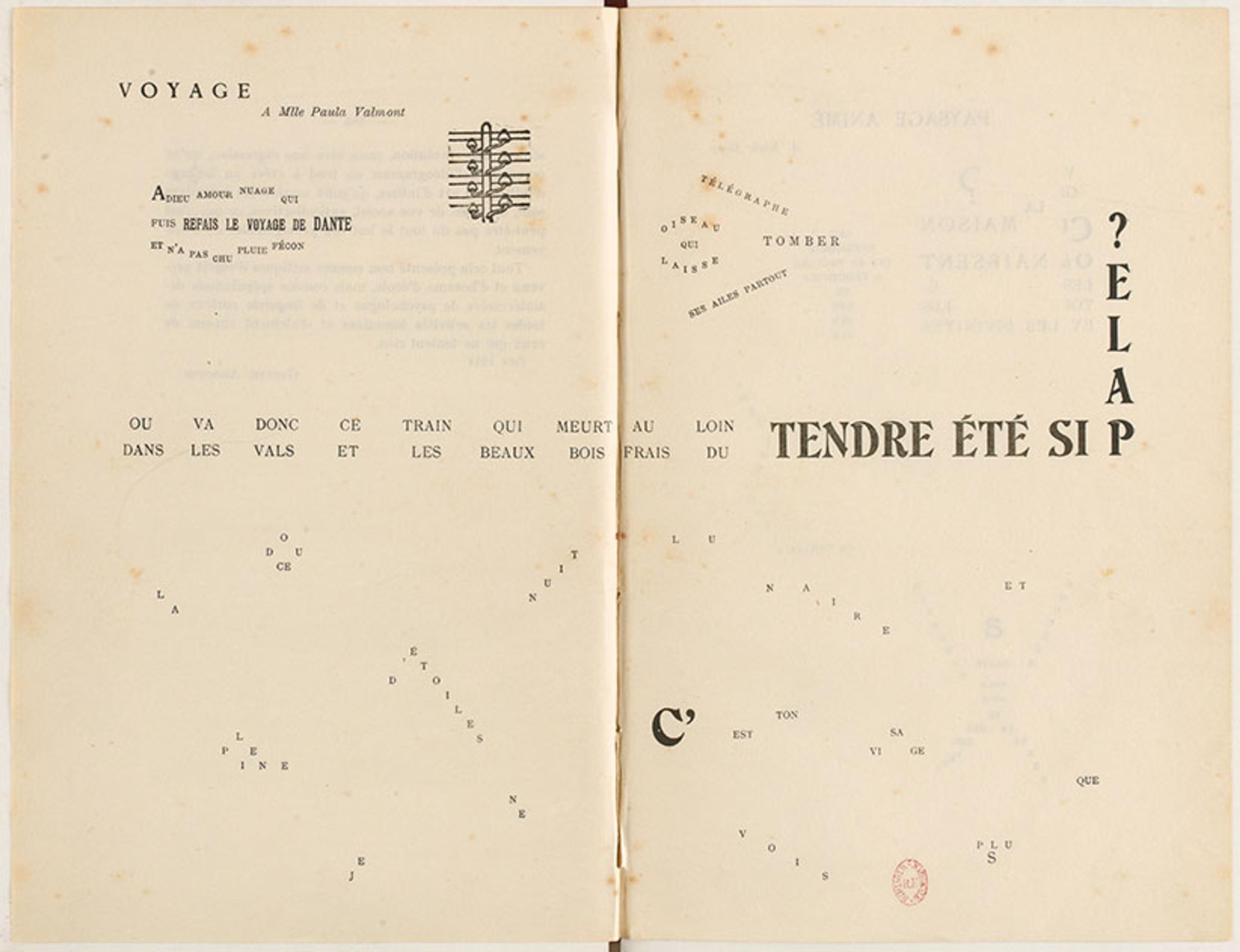

Apollinaire would continue to navigate between past and present in his later visual poetry, where the text is arranged in patterns forming an image and combined with iconography culled from other media. Among these so-called calligrammes is ‘Voyage’ (1914), which transports the mythical-religious allegory of Dante’s Inferno into the era of the railway, newspaper civilisation and mass communications. Alongside a chain of free verse in the shape of a steam train, the poem includes a graphic of a telegraph pole that Apollinaire had taken from the masthead of the newspaper Le Matin, much as his friends Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso used strips cut from newspapers in their papiers collés. For all three, the newspaper’s raw facticity and ubiquity made it an indispensable symbol of modernity.

‘Voyage’, by Guillaume Apollinaire, in the July-August 1914 issue of the magazine Les Soirées de Paris. Courtesy the BnF, Paris.

Underlying the striking intermedial collage of ‘Voyage’ was Apollinaire’s own journalism. For, as an art critic, he had become the leading defender of Cubism, a concept he helped define and popularise. His enthusiasm for modernist art even got him sacked from one reactionary newspaper. Such misadventures were typical of Apollinaire’s journalistic career, which saw him bounce from one publication to another, get caught up in a series of public feuds, and churn out countless stock-market reports while earning little more than $1,000 per month in today’s money. His activities as an art critic even led to the poet being imprisoned under suspicion of having stolen the Mona Lisa. Yet Apollinaire continually found inspiration in the rough-and-tumble of newspaper civilisation, transforming the detritus of his journalistic life into an oeuvre whose boisterous éclat recalls Mallarmé’s joyous vision of the ‘modern popular Poem’.

Proust, who benefitted from substantial inherited wealth, never had to scratch out a living from journalism. He, too, nonetheless frequently wrote for the press during the early phase of his career. Proust then reused material from these articles in his multivolume novel, In Search of Lost Time (1913-27), where culture, politics, society gossip and war are all mediated through newspapers, which the characters read and discuss obsessively.

The centrality of journalism to that semi-autobiographical portrait of the writer as an unfocused young man can be gauged from the fact that the sole piece of writing visibly completed by Proust’s Narrator is a newspaper article. Early in the novel, he jots down a description of some church steeples, which was adapted from an article about an automobile journey across Normandy that Proust had published on the front page of Le Figaro in November 1907 (to coincide with the Paris Motor Show). Having submitted this ‘little fragment’ to the same newspaper, Le Figaro, the Narrator then repeatedly scours its pages in frustration, searching for an article that seems destined never to see the light of day, until one morning – some 2,000 pages later – his mother brings him his post, including Le Figaro, which has finally published his article.

Initial excitement gives way to disillusionment as the Narrator meditates on the tensions between journalism and literature. While offering a qualified salute to journalistic ‘beauty’, he ultimately disavows journalistic publication because it is too dependent on the approbation of its readers, and therefore in conflict with the principle of art for art’s sake. That realisation helps to catalyse the Narrator’s artistic vocation, leading him to vow to write a work that will recover lost time, not for the sake of pleasing others, but to understand the self.

Unappreciative critics would get aggrieved letters from Proust, sometimes with invitations to dinner at the Ritz

Even as he disclaimed journalism, Proust drew attention to how that devalued medium had shaped his writing and accepted his ties to the press as a fundamental part of the fabric of his work and self. He both used the press as a literary laboratory and made those genetic connections to the press a central theme of his novel. Predecessors such as Balzac and Maupassant had, by contrast, passed over their own creative debts to journalism as they heaped anathema on the ‘whorehouse of thought’. After a century of evasion and resentment, Proust finally settled accounts by at once acknowledging and resisting the aesthetic hold of newspaper civilisation.

Like Mallarmé and Apollinaire, Proust also proved adept at exploiting the promotional power of the press. In collaboration with his publishers, he orchestrated extensive publicity campaigns on behalf of his books, using his contacts to obtain favourable reviews. Unappreciative critics would receive aggrieved letters from the author, sometimes accompanied by invitations to dinner at the Ritz (belying his hermitic reputation, Proust maintained an active social life until his death from pneumonia in 1922 at the age of 51). Proust even bribed newspapers to publish unsigned, self-authored puff pieces.

Flaubert had declared that artists should seal themselves off from worldly preoccupations:

One must, leaving aside material things and independently of humanity, which rejects us, live for one’s vocation, climb into one’s ivory tower and remain there, like a bayadere enveloped in her incense, alone amidst our dreams.

His successors shared his commitment to maintaining the ivory tower of artistic independence. But Mallarmé, Apollinaire and Proust did not heed Flaubert’s call to retreat into splendid isolation. Rather, they hustled to create an audience for their work and brought the dynamism of newspaper civilisation into the ivory tower itself.

What would it mean to be a hustler in the ivory tower today? The internet and its associated gadgets stir reactions remarkably like those once directed at the press. In some quarters, futurist technophilia; more commonly, alarm at the social, political and cultural impact of these innovations, combined with neurotic dependence upon them. If Flaubert were writing his Dictionary of Received Ideas today, ‘Can’t live without it, but thunder against’ could very well be the entry for ‘iPhone’. The challenge for writers as well as readers remains that of trying to come to terms with destabilising media without being dominated by them. How, in other words, can imaginative literature navigate an ocean of online text and exploit the creative potential of digital technologies?

Contemporary writers who have wrestled with versions of this question might be divided into two camps: ironic traditionalists and digital modernists. The former make the chaos of the digital era into a central theme of their writing while remaining loyal to the codex and the classic form of the comic novel. The latter write works of electronic or digital literature that are designed to be read on screens, incorporate interactive features (most commonly hypertext) and often defy conventional categorisation.

Ironic traditionalists include Gary Shteyngart, Patricia Lockwood and Lauren Oyler, who have all authored ‘internet novels’ that at once epitomise and deplore the frantic, degenerative rhythms of lives lived extremely online. Wholly or partly written in parodies of fragmented internet language, these fictional journeys into the depths of digital civilisation are characterised by searing albeit jocular pessimism about the possibility of generating any spark of enlightenment within that abyss. In Shteyngart’s techtopian allegory, Super Sad True Love Story (2010), and in Lockwood’s portrait of internet addiction, No One Is Talking About This (2021), redemption can be achieved only offline – respectively by reading ‘bound, printed, nonstreaming Media artifact[s]’ and by taking responsibility for the suffering of others. Oyler’s caustic bildungsroman of Brooklyn and Berlin literati, Fake Accounts (2021), similarly suggests that inventing a persona in real life can provide a creative antidote to the toxicity of online deception. All three depict digital media as an unsalvageable wasteland and invite us to tear ourselves away from our screens. Notwithstanding its antic, self-aware flourishes, the internet novel is pervaded by the same sense of moral nostalgia that we find in 19th-century novels of journalism such as Balzac’s Lost Illusions.

Tying a piece of writing to a phone makes it hostage to the relentless distractions of any networked device

Digital modernists – operating in the spirit of Kranzberg’s first law of technology, which states it is neither good nor bad; nor is it neutral – conversely approach digital media as a forum for playful experimentation. Just as earlier modernists adopted techniques from journalism and visual art, these authors use digital media, as Jessica Pressman puts it in Digital Modernism (2014), ‘to reform and refashion older literary practices in ways that produce new art’. Recent examples include Joanna Walsh’s Seed (2017), a coming-of-age story structured around a series of non-linear ‘vines’ that we navigate on our screens, and Kate Pullinger’s Breathe (2018), which merges data harvested from the reader’s phone into a classic ghost story, an eerie device that provides an oblique commentary on online surveillance. But the laconic, mysterious tone of such works is far removed from the all-encompassing technopessimism of the internet novel. In contrast to ironic traditionalists, digital modernists tend to resist Big Tech without rejecting its innovations. Both Seed and Breathe are published by an offshoot of Google’s Creative Lab, Editions at Play, which proclaims that these books are ‘powered by the magic of the internet’.

The instability of that ‘magic’ creates a long-term problem of technical autonomy. Many early works of digital literature from the 1980s and ’90s, composed using now-obsolete operating systems, have effectively become inaccessible. Tying a piece of writing to a computer or phone also makes it hostage to the relentless distractions of any networked device – a vastly more intrusive medium than the 19th-century newspaper. The terseness of Breathe, which can be read in under half an hour, renders that problem less acute. But it is hard to see how longer works of digital literature can overcome the steep barriers to immersive deep reading currently inherent within the form.

It might be tempting to conclude that the traditional book simply remains a superior and unimprovable medium. The basic form of the codex – bound, ink-covered pages – has proved remarkably resilient for two millennia. Despite the proliferation of e-readers and other digital supports, print continues to account for the overwhelming majority of book sales.

That picture is complicated by abundant evidence that reading is a declining pastime, especially among the young. According to the American Time Use Survey, Americans aged over 15 spent, on average, a mere 16 minutes per day reading for pleasure in 2022, down from 23 minutes in 2004. More than a third of UK adults report having stopped reading for pleasure, with a quarter of these ‘lapsed readers’ citing social media as a reason for having abandoned books. Sales of literary fiction in the UK have also plummeted since the late 2000s, in tandem with the growth of smartphone use. We may be consuming and indeed producing more text than ever before, but the aesthetic dimension of that experience has atrophied.

Books, as Maël Renouard puts it in Fragments of an Infinite Memory (2021), could well end up like horses, as ‘objects of aesthetic worship’ for a residual cultivated elite.

To check the book’s decline into genteel desuetude, we should consider drawing inspiration from the unfinished intermedial ambitions of French modernism to reimagine the form of the object itself. Faced with the rise of the newspaper, Mallarmé sought to integrate its voracious popular energy within the stable, harmonising medium of the book. In his poetry and that of his successors, that project was in practice focused on the form of the text – thence the visual echoes of newspaper headlines in A Throw of the Dice and the journalistic iconography found in Apollinaire’s calligrammes – rather than its underlying material support. Mallarmé envisioned a more extensive physical hybrid of book and newspaper. But it is, in truth, difficult to imagine how those two objects could be amalgamated into an aesthetically cohesive form.

Digital technology, by contrast, offers the potential for a genuine material transformation of the codex. Rather than viewing print and digital media as irreconcilable rivals, we could explore how they might be combined within new hybrid forms devised in the spirit of Mallarmé’s vision.

The starting point for that endeavour should be an appreciation of the codex’s enduring technological attributes. Print is not just a more aesthetically pleasing medium. Because printed books and periodicals organise text within physical space, they also have a more efficient and memorable interface. Flipping through pages is a simpler, faster and more intuitive than scrolling down a screen. And yet, throughout the internet era, innovation has been a one-way street that runs from page to screen, transforming information from analogue into digital form and thereby sacrificing the advantages of the codex – durability, beauty, flexibility, enhanced concentration – for the sake of convenience and miniaturisation.

Writers could sublimate the discombobulating modernity of the internet age

Why not preserve those virtues within an enhanced or (in Renouard’s phrase) ‘augmented’ book that imports digital technology into the codex itself? In the mid-2000s, the Greek engineer Manolis Kelaidis developed prototypes of a networked book – originally called the blueBook – that use conductive ink to create hyperlinks allowing users to access digital content on other devices by touching the pages. Advances in printed electronics have since expanded the concept’s technical possibilities. An autonomous digitally enhanced codex could incorporate hyperlinks that activate built-in micro-speakers and light up parts of the text. Other conceivable features include the ability to trigger shifting colour patterns and perhaps even moving images on the pages.

Such innovations would provide those who now seem lost to the dopamine-addled ‘Twittering Machine’ with a compelling enticement to put down their phones and enter a new fictional universe that incorporates some digital stimuli while distancing them from the neurotic distractions of the online world. And all this could be done using a sustainable, recyclable material: paper.

The prospect of paper-based augmented books also holds out the possibility of revolutionary combinations of text, image and sound that would recast the boundaries of literary art. The innovative thrust of digital modernism could be redirected towards reimagining literature’s original medium, one more hospitable than screen-based digital media to extended works of fiction and poetry and less dependent on the fickle hold of Big Tech. By combining the analogue with the digital, writers could sublimate the discombobulating modernity of the internet age into a material framework rooted in cultural antiquity, just as the French modernists channelled journalism’s unruly dynamism into the traditional structures of poetry and the novel.

‘Everything,’ wrote Mallarmé, ‘exists to end up as a book.’ The book itself should be opened up to the disorientating technologies that increasingly make up our world.

With thanks to Manolis Kelaidis for a conversation about his designs and to Maya Kulukundis for introducing me to his work.