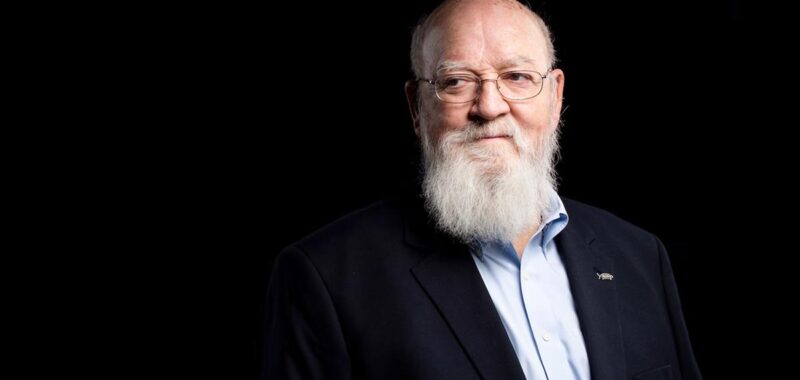

The late Daniel C Dennett (1942-2024) was a man of many parts. Sailor, sculptor, singer, pianist, raconteur, aficionado of ribald limericks, much-loved mentor to many young (and not so young) academics, trenchant critic of religion, and the prime mover behind The Philosophical Lexicon (9th ed, 2008), a dictionary of satirical neologisms based on the names of influential philosophers. Oh – and he was also a leading philosopher, coming second to Jerry Fodor (about whom more later) in a 2016 poll of the most important Anglophone philosophers of mind since the Second World War.

Dennett was a noted stylist and wordsmith too, and – unusually for a professional philosopher – he was widely read outside of academia. But to say that he was widely read is not to say that he was widely understood, and many have found Dennett’s conception of the mind opaque. What was Dennett up to – and why was his work so important?

On the received reading, Dennett was important because his work signalled a sea change in the concerns and methods employed by philosophers of mind. In the years BD (‘before Dennett’), philosophers assumed that their job was to chart the contours of our ordinary thought and talk about the mind. This approach is known as ‘ordinary language philosophy’. (Does the ‘in’ of ‘The pain is in my foot’ mean the same as the ‘in’ of ‘My foot is in my shoe’? There’s no indication that the word has changed meaning, but if ‘in’ means the same in both contexts then a pain in one’s foot must also be in one’s shoe if one’s foot is in one’s shoe.) In the years AD (‘after Dennett’), the story continues and – in large part because of Dennett – philosophy of mind divested itself of its obsession with our ordinary thought and talk about the mind, and instead took its inspiration from science – in particular, neuroscience. In the words of The Guardian’s obituary this April, Dennett ‘helped shift Anglo-American philosophy from its focus on language and concepts towards a coalition with science.’

This reading derives some support from Dennett’s telling of his own story. It was the influence of Gilbert Ryle’s Concept of Mind (1949) and Ludwig Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Investigation (1953) that drew him to Oxford in 1963 to pursue graduate studies. (‘When I was an undergraduate [Wittgenstein] was my hero, so I went to Oxford, where he seemed to be everybody’s hero.’) But a conversation with his fellow students about the experience of having one’s arm ‘fall asleep’ awakened a life-long interest in the sciences of the mind. As Dennett recounts in his autobiography, I’ve Been Thinking (2023):

… I began wondering aloud what caused it – did pressure on blood vessels starve the nerves, or was it direct pressure on nerves that shut them down temporarily? The other students looked at me as if I’d lost my mind. What did anatomy or neurophysiology have to do with this? This was a philosophical puzzle that needed analysis, not anatomy lessons. I was astonished by this lack of interest in the physical phenomenon, and after the session broke up I headed for the library to see what I could learn. That was the start of my scientific education. I ended up spending more time in the Radcliffe Science Library than in the Bodleian [Oxford’s Arts library] … I knew nothing about the nervous system, but if I was interested in the concept of mind, as I certainly was, I would have to learn about the brain.

Dennett adds that, although Ryle (his doctoral supervisor) was tolerant of his conviction, ‘he himself knew next to nothing about science, especially about neurophysiology and neuroanatomy.’

There is a kernel of truth to the received view of Dennett. The dialogue between philosophers of mind and scientists has certainly been richer and more productive in the years AD than it was in the mid-20th century, and no one can take more credit for that than Dennett. It’s also true that Dennett drew heavily on the sciences of the mind – indeed, one could acquire a decent scientific education by reading nothing but Dennett! But for all that, the received reading of Dennett is misleading, and he is an unreliable teller of his own tale. Dennett does not mark a rupture in either the concerns or the methods of philosophers, for a concern with our ordinary thought and talk about the mind was absolutely central to his project. Or so I will argue.

As the contemporary Oxford philosopher Anil Gomes observed in the London Review of Books in 2023, the key to understanding Dennett lies with another 20th-century American philosopher, Wilfrid Sellars – something of a philosopher’s philosopher. Sellars distinguished between two images of reality, the manifest image and the scientific image. The manifest image is the ordinary, everyday conception of reality – the conception of reality that human beings have prior to science. The scientific image, of course, is the conception of reality delivered by science.

The manifest image of the mind is also known as ‘folk psychology’. Folk psychology is, in effect, the mind’s natural, naive conception of itself. Unlike scientific psychology, folk psychology is independent of formal education. You grasp the essential features of folk psychology and have done so since early childhood. Folk psychology assumes the existence of a self – an ‘I’ that is the subject of thought and action. It assumes the existence of thoughts of various kinds – beliefs, desires and intentions. It assumes that we have voluntary control (‘free will’) over our actions, and that we are accountable for much of what we do. And it assumes that we are subjects of consciousness – creatures who undergo perceptual, emotional and bodily experiences.

What place can science find for these phenomena? Can we locate the self within a scientific account of the human being? What about beliefs, desires or intentions? What about free will or consciousness? Can science give an account of these phenomena in the way that it has accounted for other aspects of the manifest image (temperature, respiration, lightning) or will (some of) these phenomena go the way of the unicorns, gryphons and dragons of medieval bestiaries – entities that have no place within a scientifically informed catalogue of what there is? It is this question, more than any other, that lay at the heart of Dennett’s project.

Let’s begin with the self – this thing that acts and thinks. Some theorists conceive of selves as ‘things’ – entities that have a kind of autonomous existence in the way that shoes, ships and sealing wax do. To use one of Dennett’s terms, we might call this approach ‘industrial strength realism’ (ISR). Substance dualists (such as René Descartes) endorse a version of ISR, for they identify the self with a non-physical thing– what Ryle ridiculed as the ‘ghost in the machine’. But even those who reject dualism are often tempted by ISR, suggesting that ‘the self’ can be identified with a particular region or network in the brain.

If you don’t find ISR appealing, you might be tempted by eliminativism, the view that there aren’t any selves. As the eliminativist sees it, to believe in the self is to believe in a fiction. Eliminativists allow that talk of the self plays useful roles in ordinary life, but such talk– they argue – doesn’t refer to any genuine feature of reality. The roots of eliminativism are a philosophically novel view – it can be found in the Abhidharma Buddhist texts of the 3rd century BCE – but its contemporary influence is due to science. Science, so the argument goes, doesn’t tell us what selves are – it tells us that they aren’t.

Although ISR and eliminativism disagree on whether selves exist, they have a shared conception of what it would take for selves to exist. Both positions assume that talk of the self involves an attempt to latch on to a particular entity – a thing of some kind. (The advocate of ISR assumes that this attempt is successful, whereas the eliminativist takes it to be failure.) Dennett rejected that assumption, arguing that it fails to understand the commitments of folk psychology (‘the manifest image’). Folk psychology doesn’t assume that selves are (or would need to be) particular things in the way that (eg) shoes, ships and sealing wax are. Instead, Dennett argued, folk psychology treats selves as ‘abstracta’ – theoretical devices such as centres of gravity.

To ask which bit of the brain is the self is as confused as asking which bit of a chair is its centre of gravity

A chair’s centre of gravity, Dennett pointed out, is real, but it isn’t real in quite the same way that the chair is. It doesn’t take up space in the way that the chair (or its parts) do, nor is it causally related to other objects in the way in which the chair is. When moving house, you might want to check that the removalists have loaded your chairs and tables into the truck, but you don’t need to check that they’ve also loaded their centres of gravity. (Load the chairs and tables, and you’ll get their centres of gravity for free.)

Selves, Dennett suggested, are ‘centres of narrative gravity’. They are the abstract points around which a person’s mental life is structured. Like centres of physical gravity, they are devices that we employ in order to ‘understand, and predict, and make sense of, the behaviour of some very complicated things’ – namely, us. Selves are real, but they aren’t real in the way that things are. Indeed, selves couldn’t be things, for the concept of the self isn’t in the business of picking out things. To ask which bit of the brain is the self would be as confused as asking which bit of a chair is its centre of gravity. Taking the question seriously shows that one has failed to grasp the nature of the relevant concept.

Was Dennett’s analysis of the self grounded in brain science (‘if I was interested in the concept of mind … I would have to learn about the brain’), or did it have some other basis?

It was certainly informed by his understanding of brain science. Neuroscience, Dennett argues, tells us that multiple streams of processing occur in parallel, and there is no one place in the brain where it ‘all comes together’. But for all that, the heavy lifting in Dennett’s account of self was done not by his account of the manifest image of the mind. Ryle, Wittgenstein and other ‘ordinary language’ philosophers enjoined us to pay close attention to the texture of folk psychology. Dennett took their advice to heart. His picture of what selves are – of what they must be– was grounded not in neuroscience but in armchair reflection on what our ordinary thought and talk about the self commits us to.

Indeed, if Dennett’s analysis of the self was driven by anything, it was driven not by science but by stories – and by stories about stories. At the heart of his paper ‘The Self as a Centre of Narrative Gravity’ (1992) is a story about a story-writing machine:

a computer that has been designed or programmed to write novels. But it has not been designed to write any particular novel. We can suppose (if it helps) that it has been given a great stock of whatever information it might need, and some partially random and hence unpredictable ways of starting the seed of a story going, and building upon it. Now imagine that the designers are sitting back, wondering what kind of novel their creation is going to write. They turn the thing on and after a while the high-speed printer begins to go clickety-clack and out comes the first sentence. ‘Call me Gilbert,’ it says.

At this point, ‘Gilbert’ (Ryle again, perhaps?) doesn’t refer to anything – it’s a word that has no use in the language. But suppose – Dennett continues – we were to put this story-telling computer in a robot, and give the robot ways of interacting with the world. And suppose we were to ensure that the words that emanate from this robot – its account of what ‘it’s’ up to – more or less match its behaviour, so much so that this speech starts to constrain not only its behaviour but our own. (Gilbert says: ‘I’m off to the supermarket,’ and so you ask it to pick up a loaf of bread for you.) At this point, Dennett suggests, ‘Gilbert’ has acquired a role in our language not unlike that acquired by your name or mine. A self has emerged. As he puts it: ‘the patterns in the behaviour that is being controlled by the computer are interpretable, by us, as accreting biography – telling the narrative of a self.’

Among other things, selves have beliefs, desires and intentions. Mr Brown believes that it’s going to rain tomorrow. Ms Green wants to visit Greece for her summer holidays. Dr Pink intends to prune her roses at the weekend. Beliefs, desires and intentions – what philosophers call ‘intentional states’ – are central to the manifest conception of the mind. Can a place be found for them in the scientific image of the mind? If so, what might that place be?

Jerry Fodor – Dennett’s one-time sailing partner, later his sparring partner – defended one influential answer to this question. According to Fodor, beliefs, desires and intentions are sentences in a language of thought. What it is to believe that it’s going to rain tomorrow is, roughly, to have a brain state that represents tomorrow’s weather and guides one’s behaviour in the distinctive ways that beliefs do. Rather than being realised by marks on paper or patterns of sounds in the way in which natural language sentences are, beliefs, desires and intentions are sentences written in the brain.

A very different take on the prospects of intentional states was defended by Paul and Patricia Churchland. The Churchlands shared Fodor’s assumption that intentional talk attempts to capture the underlying causal structure of the mind, but they didn’t share his optimism about its prospects of success, arguing that it is a miserable failure. In their view, folk psychology’s appeal to beliefs, desires and intentions won’t be vindicated by the sciences of the mind – they will be eliminated.

Dennett rejected both Fodor’s realism and the Churchlands’ eliminativism. In his view, both approaches are guilty of a common failing: they misconstrue the point of intentional-state talk. Drawing on the work of his mid-century heroes – most notably Ryle – Dennett argued that we appeal to beliefs, desires and intention, not because we are looking to identify the internal causes of behaviour, but to make sense of it. The aim of intentional talk is to render human agency comprehensible, not to reflect the causal structure of the brain.

Dennett argued that beliefs and desires are patterns, and patterns are perfectly objective features of reality

Dennett called his view ‘intentional systems theory’. At its heart was something that he called the ‘intentional stance’:

Here is how it works: first you decide to treat the object whose behaviour is to be predicted as a rational agent; then you figure out what beliefs that agent ought to have, given its place in the world and its purpose. Then you figure out what desires it ought to have, on the same considerations, and finally you predict that this rational agent will act to further its goals in the light of its beliefs. A little practical reasoning from the chosen set of beliefs and desires will in many – but not all – instances yield a decision about what the agent ought to do; that is what you predict the agent will do.

In Dennett’s hands, intentional systems theory isn’t just an account of how we ascribe beliefs, desires and intentions to each other – it’s an account of what these things are. All it takes to qualify as an intentional system – a ‘true believer’, as Dennett once put it – is to display the kinds of behavioural patterns that enable the intentional stance to get a genuine grip.

Dennett’s critics argued that his ‘mild realism’ was realism in name alone, and that he was in effect treating intentionality as nothing more than a useful fiction. This criticism was encouraged by Dennett’s talk of ‘stances’, which seemed to suggest that we project intentionality onto reality, much in the same way in which the equator is projected onto the globe. Dennett resisted this reading of his view, arguing that beliefs, desires and intentions are patterns, and patterns are perfectly objective features of reality. To make this point, he retold a tale first told by the philosopher Robert Nozick.

Suppose, Nozick had suggested, we encounter a species of Martians who can predict our behaviour based on their comprehensive knowledge of physics. They look at Wall Street, and where we see:

… brokers and buildings and sell orders and bids, they see vast congeries of subatomic particles milling about – and they are such good physicists that they predict days in advance what ink marks will appear each day on the paper tape labelled ‘Closing Dow Jones Industrial Average’. They can predict the individual behaviours of all the various moving bodies they observe without ever treating any of them as intentional systems. Would we be right then to say that from their point of view we really were not believers at all? … If so, then our status as believers is nothing objective, but rather something in the eye of the beholder – provided the beholder shares our intellectual limitations.

Dennett argued that, although Nozick’s Martians can predict our behaviour, in failing to grasp the patterns that underwrite the intentional stance, their knowledge of reality omits something of importance. These super-smart (but intentionally blind) Martians are like toddlers who see a $10 note but fail to grasp its purchasing power.

Dennett’s account of intentionality is controversial, and many argue that it fails to treat intentional states with sufficient seriousness. Genuine intentionality, it’s often said, requires more than behavioural patterns. (Indeed, in a piece published in The Atlantic less than a year before his death, Dennett himself provided reasons to doubt the adequacy of his account: although it’s almost impossible to resist taking the intentional stance towards ChatGPT and other large language models, that fact doesn’t settle the question of whether such systems have intentional states.) But controversial or not, there’s no denying the power and elegance of Dennett’s account. And, crucially, it’s not a conception of intentionality that emerges from the sciences of the mind. Instead, the heavy lifting in his approach is done not by his take on scientific psychology, but by his take on the demands of folk psychology. He is, in this respect, firmly embedded in the ‘ordinary language’ tradition of Ryle and Wittgenstein.

Of all the topics on which Dennett wrote, his views on consciousness are perhaps the most controversial – and hardest to pin down. Some theorists consider Dennett as espousing eliminativist views about consciousness – making him a ‘consciousness denier’, as Galen Strawson once put it in The New York Review. (Strawson went on to describe eliminativism as ‘the silliest claim ever made’.) There are certainly eliminativist elements to Dennett if one looks hard enough. (His early paper ‘Why You Can’t Make a Computer That Feels Pain’, 1978, argued for that claim on the grounds that the folk concept of pain is too confused to refer to anything – computers don’t have pains because there are no pains to be had!) But, for all that, Dennett was no consciousness denier. To understand why, we need to consider the curiously named ‘Quining Qualia’ (1988), arguably his most important paper on the topic.

The Philosophers’ Lexicon – first published by Dennett a decade before ‘Quining Qualia’– defines ‘to quine’ as to deny ‘resolutely the existence or importance of something real or significant’. Dennett coined the term in homage to his undergraduate advisor W V O Quine, who had tried to construct a metaphysics with as few entities as possible. That’s ‘quining’; what about ‘qualia’? Dennett distinguished two senses of this term. In one sense, qualia (singular: quale) are simply the ways that things seem to us in perceptual experience. (To use Dennett’s example, consider how a glass of milk looks at sunset – that’s a quale.) To deny that there are ways the world appears to us in perceptual experience would indeed be in the running for ‘the silliest claim ever made’, but Dennett made no such claim. Instead, his eliminativism was directed towards a certain conception of perceptual experience – Qualia-with-a-capital-Q. To believe in Qualia is to think that the experiential character of consciousness (‘the ways things seem to us’) involves properties that are intrinsic, private, ineffable and directly available to introspection. It is Qualia – and not qualia – that Dennett quined.

How did Dennett attempt to undermine the appeal of Qualia? He told another story.

Chase and Sanborn have worked as coffee tasters for decades. One day, they both complain that something has changed in their experience of the coffee, but they describe that change in different ways. Chase says that, although the flavour of the coffee hasn’t changed (its Quale is unchanged), he no longer likes that flavour; Sanborn says that his preferences haven’t changed, but that the coffee no longer tastes the way that it used to (its Quale is different). Dennett argues that although Chase and Sanborn seem to offer contrasting accounts of what’s happened to them, that appearance is an illusion, for nothing available to either science or introspection could distinguish between these proposals. The taste of coffee is not independent of our responses and reactions in the way that Qualia would need to be.

When Dennett did offer a positive view of consciousness, he leant heavily on metaphors and literary allusion

Note, in passing, the absence of science here. There is no mention of single-cell recordings; no appeal to computational models of brain activity; no measures of entropy. Instead, we’re asked to consider a purely fictional scenario. Dennett’s case against Qualia rests on a purely philosophical argument that would not have been out of place in the 1950s. (Indeed – as Dennett himself points out – it is a variation on a purely philosophical argument that was given in the 1950s: Ludwig Wittgenstein’s ‘beetle in the box’ argument.) Although there is background concern here with scientific methods – in effect, Dennett is challenging the Qualia-phile to explain how Qualia might be studied – nothing in the way of ‘brain learning’ is assumed.

Dennett’s rejection of Qualia wasn’t a rejection of consciousness – it was a rejection of a certain conception of consciousness. But if Dennett didn’t reject consciousness, what explanation did he provide of it?

Here, I think, is where Dennett is most elusive. In part, this is because his focus tended to be critical rather than constructive. As the subtitle of one of his books puts it, he wanted to remove ‘philosophical obstacles to a science of consciousness’, such as the idea that consciousness involves an inner observer, or that we need first-person methods to study consciousness, or that our intuitions about consciousness are trustworthy. When he did offer a positive view of consciousness, he tended to lean heavily on metaphors and literary allusion. Consciousness Explained (1991) paints a picture of consciousness as a ‘[James] Joycean machine’, in which the stream of consciousness emerges from the jostling between multiple (representational) drafts. In later essays these descriptions give way to a new set of metaphors – consciousness as ‘fame in the brain’, consciousness as ‘cerebral celebrity’, consciousness as ‘clout’.

How should we understand these metaphors?

In places, Dennett seems to treat them as placeholders for precise, empirically informed constructs. On this view, there is an account of what ‘fame in the brain’ really involves, and it’s the job of science to discover that account. Dennett even suggested that science had already made significant strides towards that goal, pointing to what he saw as an emerging consensus in favour of the global neuronal workspace model of consciousness.

‘Multiple Drafts is not just the name of my consciousness model; it describes my thinking and writing process’

In other places, however, Dennett seemed to deny that these metaphors can be traded in for sharper, scientifically grounded constructs. That strand of Dennett’s thought is perhaps most evident in connection with his claim that:

… consciousness is more like fame than television; it is not a special ‘medium of representation’ in the brain into which content-bearing events must be ‘transduced’. It is rather a matter of content-bearing events in the brain achieving something a bit like fame in competition with other fame-seeking (or at any rate potentially fame-finding) events.

One can be on television and be seen by millions of viewers, and still not be famous, because one’s television debut does not have the proper sequelae. Similarly, there is no special area of the brain where representation is, by itself, sufficient for consciousness. It is always the sequelae that make the difference.

Dennett claims that it’s a representation’s sequelae – its effects on thought and action – that matter, but which sequelae matter? After all, unconscious events also have effects on thought and action. Should we look to science for an account of which sequelae are required for genuine neural fame? But how would science fix that boundary? ‘No bright line,’ he wrote in Sweet Dreams (2005), ‘need distinguish true fame from mere behind-the-scenes influence.’ Expecting science to tell us where unconsciousness ends and consciousness begins, Dennett seemed to suggest, would be as pointless as expecting it to tell us where local celebrity ends and true fame begins.

The contrast between these two views is profound. One gives consciousness a place at the table of science, putting it alongside other scientific constructs such as action potentials, inhibition and episodic memory. The other restricts it to folk psychology, suggesting that the scientific study of the mind has no more use for the notion of consciousness than the scientific study of plants has for the notion of a weed. I am not sure which of these two views Dennett really held – indeed, it is not clear to me that he had a settled view on this issue. As he observed in his memoir: ‘Multiple Drafts is not just the name of my consciousness model; it describes my thinking and writing process.’

‘The aim of philosophy, abstractly formulated,’ Sellars said, ‘is to understand how things in the broadest possible sense of the term hang together in the broadest possible sense of the term.’ Paraphrasing Sellars, we might characterise Dennett’s own thought as the attempt to understand how the folk image of the mind ‘hangs together’ with the scientific image of the mind. There are, of course, two ways of tackling that question. One can work from the science end of things, asking what exactly the scientific image of the mind involves. Alternatively, one can work from the folk end of things, asking what the ordinary, everyday conception of the mind involves.

Dennett had important things to say about the scientific image of the mind, but that’s not why he matters. Dennett matters because of what he had to say about the commitments of folk psychology – about what our everyday thought and talk about persons requires for its legitimacy. Dennett was quite willing to reject those aspects of folk psychology that he took to be at odds with science; as he once remarked in connection with free will, his aim was ‘saving everything that mattered about the everyday concept of free will, while jettisoning the impediments’. But in Dennett’s view, relatively little of folk psychology is beyond salvation. What needs to go is not so much folk psychology (whose commitments are relatively shallow), but the gloss on folk psychology that philosophers have imposed on it. In that regard, Dennett doesn’t mark a radical rupture in the aims or methods of philosophy of mind, but instead belongs firmly in the tradition of his mid-century heroes, Ryle and Wittgenstein.