Chilean director Pablo Larraín has carved out a niche for himself creating portraits of iconic women on the edge of a nervous breakdown at significant moments in their lives. First there was Jackie (Kennedy, in the four days before her husband’s funeral), then Spencer (Princess Diana, during a fateful visit to one of the queen’s country estates), and now Maria—as in Callas, the renowned opera diva, in the days before her death.

The first two films feature women whom we feel we know because their image is so ubiquitous, but in fact, what most of us “know” of them is supposition and projection. Callas at least has a body of work to aid our understanding, and she chose—indeed fought for—her place in the limelight. Larraín leans into this, creating not a conventional biopic narrative based on a linear account of events, but rather an associative excursion into his subject’s imagined inner life—her dreams, fears, and desires.

For Callas, he has imagined a sort of reclusive, Sunset Boulevard–like existence, with the diva drifting around her lavish Paris apartment—complete with a devoted butler/chauffeur/nursemaid (Pierfrancesco Favino), assisted by an equally devoted housekeeper (Alba Rohrwacher)—as she casts her mind back to past triumphs. The two servants try to get Callas to eat and cut down on prescription medication consumption while catering to eccentricities, like moving a grand piano around the apartment’s grand salon, as directed, on a regular basis.

Angelina Jolie’s preparation for the part encompassed taking operatic singing lessons for seven months, with the result that her singing voice is blended with Callas’, mostly in scenes depicting the diva after her voice is in decline. (The music in scenes re-creating Callas’ legendary performances in her prime are from original recordings.) Jolie gives a committed performance, but she can’t help the distracting, nearly otherworldly perfection of her looks (set off by a wardrobe that will have fans of vintage midcentury French couture sighing with bliss). The real Callas, by contrast, was striking, glamorous, and elegant, but not a classical beauty like Jolie.

While we can’t claim to know what was going through Callas’ mind as she neared the end, we can nevertheless examine how much the external world referenced in Maria resembles the real thing.

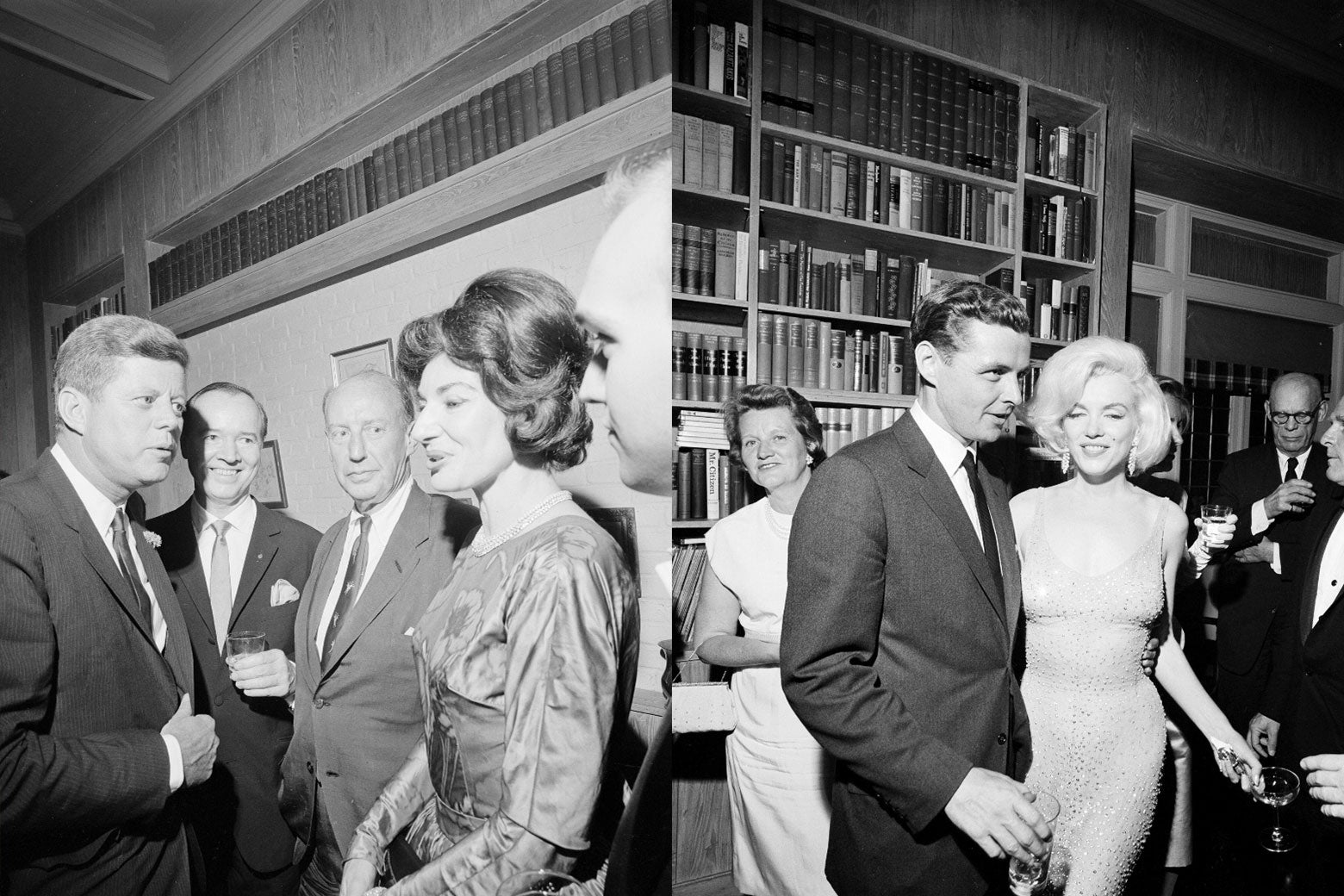

Photo illustration by Slate. Photos by Cecil Stoughton, White House Photographs, and John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston.

Did Maria Really Have Two Devoted Employees?

In the film, Maria’s butler, Ferruccio, and her cook/maid, Bruna, are as much family as staff, with Maria never happier than when she’s eating with them (or, rather, watching them eat) in the kitchen, then playing cards together. They, in turn, try to protect her from intrusive reporters and paparazzi.

The depiction of Callas’ close relationship with her household staff is accurate. After serving in the Italian military, Ferruccio Mezzadri went to work for Callas in 1958 and spent the next 20 years in her employ. Still alive, he has refused large sums of money to dish the dirt (although he did speak to Larraín and screenwriter Steven Knight), but he has often spoken of the kindness Callas showed to him and Bruna Lupoli.

That Callas thought of the two as her chosen family was confirmed when film and opera director Franco Zeffirelli, Callas’ close friend and artistic collaborator, declared in a 2004 interview with Italian news channel TG5 that two people had told him “Callas wrote a will leaving half her estate to her maid and her driver, and the rest to a Milan retirement home. But no will of that kind was found, I believe it was burnt.” In fact, Callas’ estate, thought to be worth around $12 million, was divided equally between her ex-husband Giovanni Battista Meneghini and her estranged sister Yakinthi, with Yakinthi later saying she gave her share of the inheritance to Mezzadri and Lupoli, but whether she actually did so is unknown.

Noting that no autopsy was ever conducted to determine the cause of Callas’ death, Zeffirelli floated the dramatic possibility that Callas might have been poisoned by “a group of strange Greeks who were connected to her sister and whom Callas hated.” (No proof has surfaced to back up any of Zeffirelli’s assertions.) He was undoubtedly referring to Callas’ rehearsal pianist in the final years of her life, Vasso Devetzi, observing that Devetzi had unilaterally arranged for Callas’ body to be cremated. Devetzi was also widely believed to have stolen a large amount of money from Callas to start an educational foundation for voice students, which she eventually did. Zeffirelli may have been reacting to the auction of Callas’ jewels a few days before he gave the aforementioned interview, which netted more than 1.4 million pounds for an anonymous seller rumored to be related to Devetzi, who had herself died by then.

Did Maria’s Mother Make Her Sing for Nazi Soldiers During World War II?

In a flashback, Maria recalls her family starving in occupied Athens during World War II, when Maria’s mother invites two German soldiers into their house and urges a young Maria and Yakinthi to be nice to them. The soldiers are interested mostly in the prettier Yakinthi, but then Maria realizes she can be rewarded for singing for them, and soon Nazi officers are dropping by regularly to hear the young Maria sing.

In fact, Callas could have voted for John F. Kennedy because she was born in New York, but when she was 13, the family moved back to Athens just in time for World War II. They were indeed starving during the occupation, reduced to rummaging through garbage bins looking for something to eat, and her mother did force her to sing for enemy soldiers in exchange for food, giving Callas a choice between performing and prostitution. “Callas resented her mother, who worked as a prostitute during the war, for trying to pimp her out to Nazi soldiers,” Lyndsy Spence, a Callas biographer, told the Guardian.

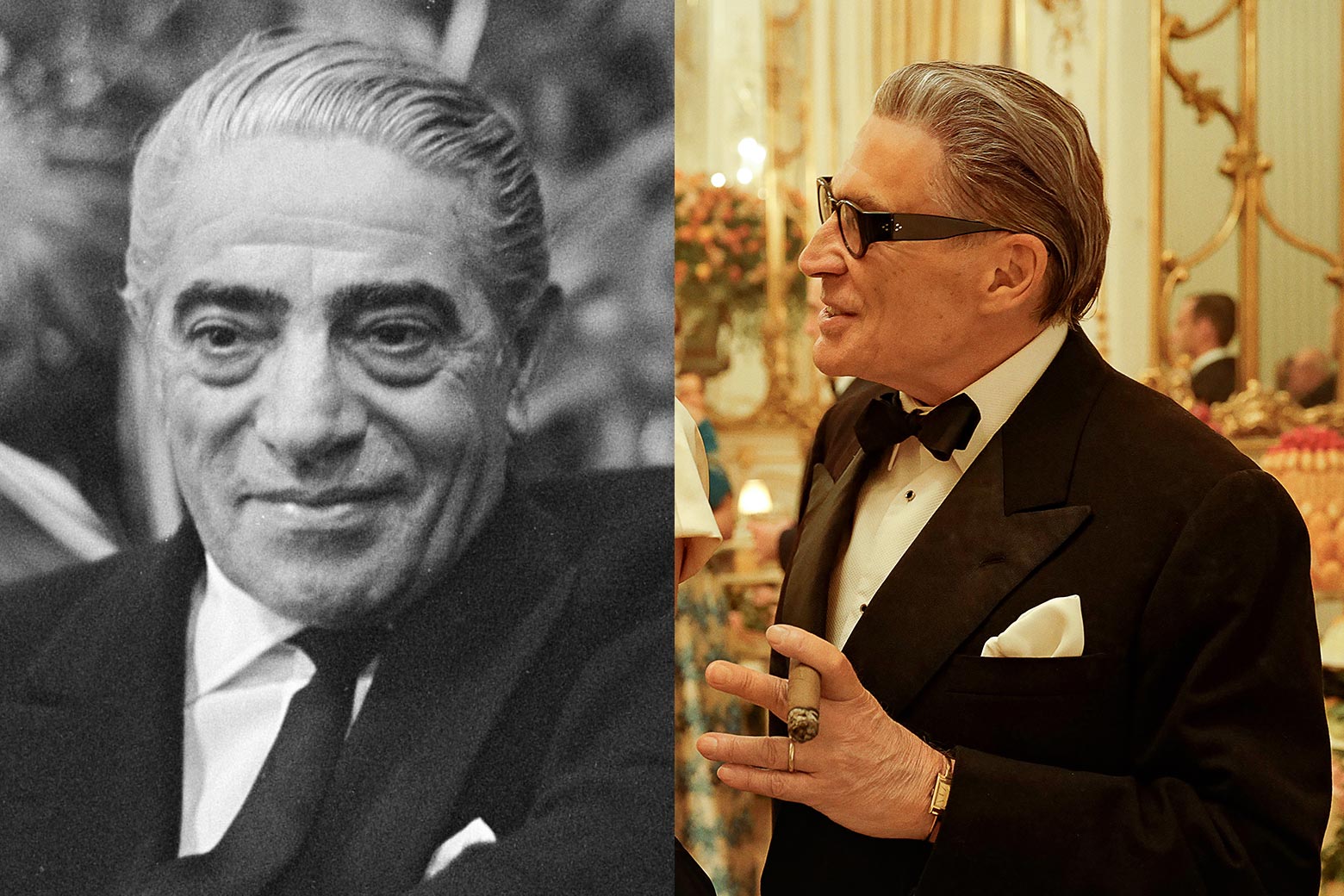

Photo illustration by Slate. Photos by Pieter Jongerhuis/Wikipedia and Pablo Larraín/Netflix.

Did Maria Die of an Autoimmune Disease?

In the film, it’s not clear what Maria’s illness is, except that it seems to require, she thinks, her taking a large amount of prescription drugs. However, she is not so ill that she is unable to go for walks through Paris immaculately dressed and accessorized. Flashbacks reveal that she has struggled with her health for many years, to the point of having to cancel long-booked appearances and sometimes going on regardless and collapsing onstage, both of which hurt her reputation for professionalism. At one point, a doctor tells Maria’s butler Ferruccio that he is prescribing prednisone, a steroid, to combat an autoimmune condition that is causing her heart to fail. In an echo of The Red Shoes, the doctor also says that if Maria continues to try to sing, it will kill her.

Officially, heart failure was listed as the cause of Callas’ death. However, according to Spence, who had access to her unpublished letters, Callas had suffered from dermatomyositis, a deteriorative autoimmune condition related to muscular sclerosis, for many years. Symptoms may include aches and pains, fatigue and insomnia, vertigo, low blood pressure, muscle weakness, and glaucoma (which affected Callas’ vision). The condition also affects the central nervous system and would explain why Callas lost control of her voice in the 1950s, although she was not diagnosed with the illness until 1975.

Callas had taken the opera world by storm in 1948 and reigned as its leading soprano for a decade, but in 1958 her voice almost cracked while she sang Norma in Rome with the Italian president in the audience; the crowd responded with derision instead of its usual adulation. Then, in 1962, her voice cracked while she was singing Medea at La Scala, due, Spence wrote, to fluid on her vocal cords. In 1965, when she was 41, Callas’ voice gave out during a performance of Norma in Paris, and she collapsed backstage. That year, she gave her final performance in a full-length opera (Tosca, her signature role), though she continued giving vocal recitals until 1974.

Callas’ loss of vocal tone and range has also been attributed to singing too often and too ambitiously, or to a drastic weight loss (she weighed 200 pounds at the start of her career but lost half her body weight after receiving iodine injections into her thyroid gland), but it is more likely that these factors exacerbated the effects of the disease rather than undermining her voice on their own. However, her punishing performance schedule did lead to a dependence on prescription drugs. “In the 1950s, when she was completely overworked, her husband [Meneghini, an Italian industrialist who was also her manager] put her in touch with a doctor who gave her ‘liquid vitamins’—speed. It worked for a time, she could go and sing everywhere,” Spence said.

In 1956 Callas met Greek shipping tycoon Aristotle Onassis and, in 1959, left Meneghini to live with him. He introduced her to Mandrax, the sedative known in the U.S. as Quaalude, which calms the nervous system and helped with her dermatomyositis symptoms, but she became addicted and had a few accidental overdoses. After her diagnosis and the prescription for steroids in 1975, she was able to ditch the downers, writing to her godfather: “Now with his cure, I am much calmer. Pills, of course, but good ones, not heavy drugs.” But unfortunately, she stopped taking the prescribed medication because it made her gain weight, and she returned to self-medicating with Mandrax, which she obtained from her sister Yakinthi (by mail from Athens, not in person as the movie suggests) and the untrustworthy Vasso Devetzi. Although steroids can increase the risk of heart failure, Mandrax overdoses have been linked to cardiac arrest.

Was Maria Secretly Recorded Rehearsing at a Paris Theater?

In the film, without telling anyone where she’s going, Maria slips out in the afternoons to a small theater where sympathetic British accompanist and vocal coach Jeffrey Tate runs through “Habanera” from Carmen with her, mostly for her own pleasure rather than with any intention of public performance. Unbeknownst to her, a couple of French journalists have gotten wind of these sessions and sneak into the theater to make a recording, intending to play on the radio the once-great diva’s shadow of her former voice. Fortunately, the faithful Ferruccio sees the journalists laughing outside the theater and wrests the tape away from them.

Callas, who was mulling over giving a solo concert with the Philharmonia Orchestra in London in late 1976, did indeed start rehearsing at the Champs-Elysées theater with Tate at least a year before her death. Tate, a former vocal coach and accompanist at the Royal Opera House, where he met Callas, was a featured guest conductor at opera houses across the world. (After he died, in 2017, his ashes were scattered from Venice’s Maria Callas Bridge.) During these rehearsals, Callas herself made trial recordings of “Habanera,” as well as Beethoven’s aria “Ah! Perfido.” But, dissatisfied with the sound of her voice, she refused to continue after recording only two-thirds of the aria. In December 1980, a French radio channel broadcast these recordings, leading Callas’ heirs—her estranged mother and sister—to sue both the radio station and the theater manager who had provided the recordings.

Callas made one more recording, a rehearsal session taped at her home a few weeks before her death, accompanied by Devetzi on the piano.

Photo illustration by Slate. Photos by U.S. Department of State in the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston, and Netflix.

Did Callas Meet Marilyn Monroe at JFK’S 45th-Birthday Concert?

In the film, Onassis and Maria attend the legendary concert for President Kennedy’s 45th birthday at Madison Square Garden, during which Marilyn Monroe sings a breathy version of “Happy Birthday to You” clad in a skintight dress. At a glamorous party after the show, Maria has a conversation with Marilyn about the challenges of a life in the spotlight.

Callas not only attended the concert, but she sang two arias from Carmen at it. She certainly attended the after-party at the home of Arthur Krim, the head of United Artists, and she certainly met Monroe (the two were photographed together), but it’s unknown whether they had a heart-to-heart. At any rate, in her book Maria Callas: An Intimate Biography, author Anne Edwards asserts that Callas went to the party against her better judgment (and with a friend called Costas Gratsos, not Onassis), becoming keen to leave early because Monroe was taking all the focus. Kennedy caught sight of her standing alone, Edwards wrote, and told a Time magazine correspondent: “Go talk to Callas. No one’s talking to her. She’s pouting.”